What is happening with the position of the Latin American countries regarding the Summit of the Americas–held in Los Angeles from June 8 to 10–shows that Biden’s calculations have failed to include a definitive factor: The international system has changed and the U.S. role in it has changed, which means that the characteristics that could make that system of alliances work are no longer the same.

Starting with the U.S. itself: In a cost-benefit relationship, during the last administrations it has become evident how little interest the U.S. has in what was previously called its “backyard.” The administration of Donald Trump was decisive in this realization, not only because of proposals such as the wall that he planned to build, but also with the attitude of indifference toward the region. In the Biden administration, this attitude was expected to change. However, not only have its statements and policies against Latin American migration remained very strong, but the Biden administration has also not concealed the utilitarian and double-standard vision it has of Latin America, seeing it as one more piece in the war it has declared against China, with the aim of maintaining itself as the hegemonic power of the international system.

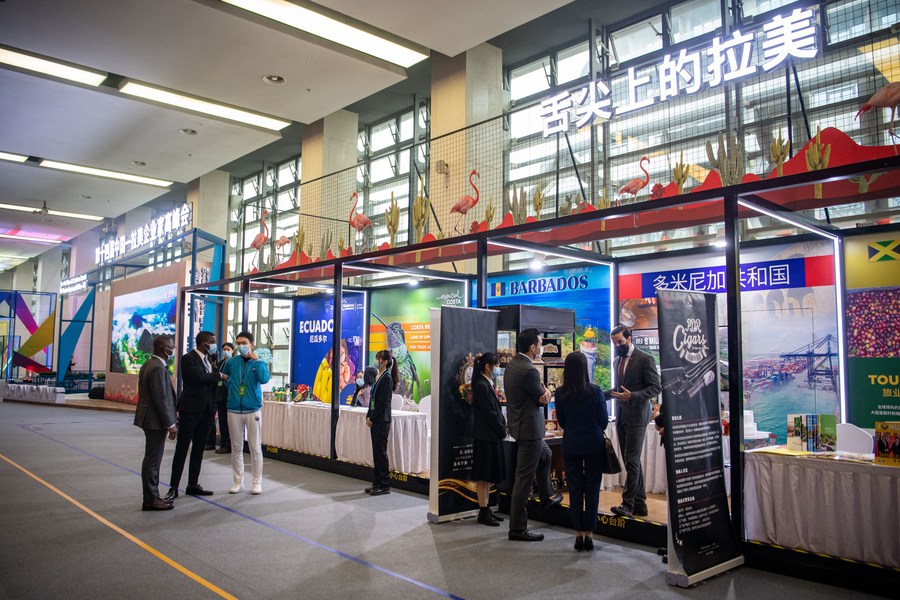

In this context, many countries in the region are seeing more costs than benefits in their relationships with the U.S., especially if one considers that China has effectively become the second most important trading partner in the region, with all its willingness to invest and cooperate in favor of the development of the countries, with non-coercive forms of relationship, offering Latin American countries an alternative.

The Biden administration continues to believe that it can maintain its traditional coercive methods to manipulate the region. Along these lines, President Biden decided not to invite Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela to the summit, arguing that they do not respect human rights or democracy. However, Colombia, the country with one of the highest rates of human rights violations in the region, was invited. The reason? Colombia is a consolidated ally of the U.S. The message behind this attitude of the Biden administration was not well received by several Latin American countries, starting with Mexico. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said that all countries in the region should be invited to the Summit of the Americas, not just U.S. allies.

A boycott of the Summit?

It is the first time, since the Summit of the Americas opened in Miami in 1994, that the U.S. is the host again. Various officials in charge of organizing the event have tried to divert attention from those invited to the Summit, and to put it on the results that are expected from it. One official even told the BBC anonymously that ultimately the host has the right to decide who to invite and who not to invite, so guests should feel honored rather than criticizing the event.

But there are more than a few Latin American countries that have spoken out against the exclusion that the U.S. is carrying out. In addition to Andrés Manuel López Obrador from Mexico, Alberto Fernández from Argentina and Luis Arce from Bolivia also expressed their disagreement. Arce said that a “Summit of the Americas without all the countries of the continent is not a Summit of the Americas.” While countries like Chile and Argentina criticized the decision, but still confirmed their attendance at the event, others like Mexico, Bolivia, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala decided not to attend despite being invited. That means that–adding Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba–eight countries are not present.

The U.S. said it was reviewing the possibility of inviting officials from these countries, but we are talking about the highest-level event in the region, so having a Deputy Minister or Foreign Minister is not the same as having a President. Even so, the absence of these countries, beyond setting a precedent and showing a Latin America that is not willing to accept the conditions imposed by the U.S. so easily, have not stopped the Summit from being held.

The cost of absences

Andrés Manuel López Obrador openly said that he is sure that not attending the Summit will not cause damage to bilateral relations between Mexico and the U.S. Nevertheless, allowing some countries in the region to be excluded from such an important event does have very large costs for the autonomy of Latin America. The leaders of other countries think the same way.

The concern of the U.S. officials in charge of the event goes further, since the issues to be discussed are precisely the sensitive issues that affect the entire region, such as migration, and economic and development issues, in addition to the traditional issues of the Summit, such as the promotion of democracy, social inclusion and commercial competitiveness in the region. But it is precisely this concern that outrages the leaders of the countries that have decided not to attend, since no Latin American country can be excluded from these issues, much less because of a manipulation of power by the host.

The Summit of the Americas is taking place and probably some of the agreements that emerge from the meeting will later be communicated bilaterally to the absent countries. So, beyond the event, what is very important to highlight about this situation is the evidence of the decrease in the U.S.’ ability to influence, as well as an increasingly independent position of Latin American countries with respect to the discourse of enemies and alliances proposed by the U.S.

At a time when the Biden administration’s strategy to contain China’s development is to promote that dichotomous vision of the Cold War, a Latin America more inclined to Active Non-Alignment, open to continuing to deepen strategic relations with China and other countries without falling into that exclusionary dynamic, not only shows us countries that are putting their interests above those of the U.S., but also a region that increasingly seeks its autonomy. This is the least convenient outcome for the Biden administration at this time, but it is the best thing Latin America can do if the region wants to break its bonds of dependency.

The author is a sinologist, internationalist and research professor at Externado University of Colombia.